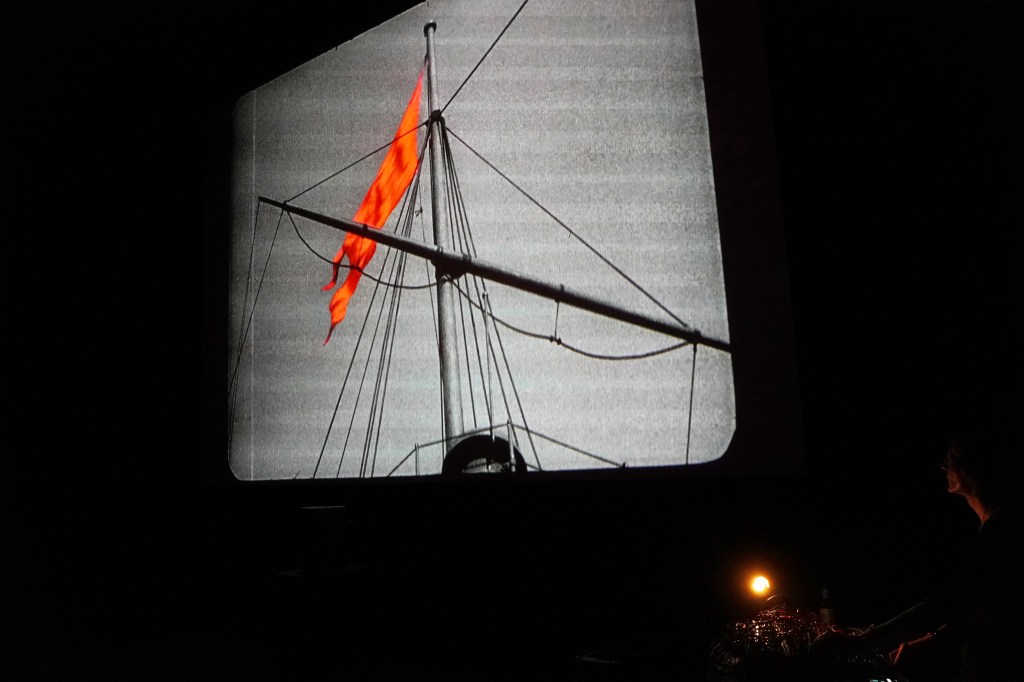

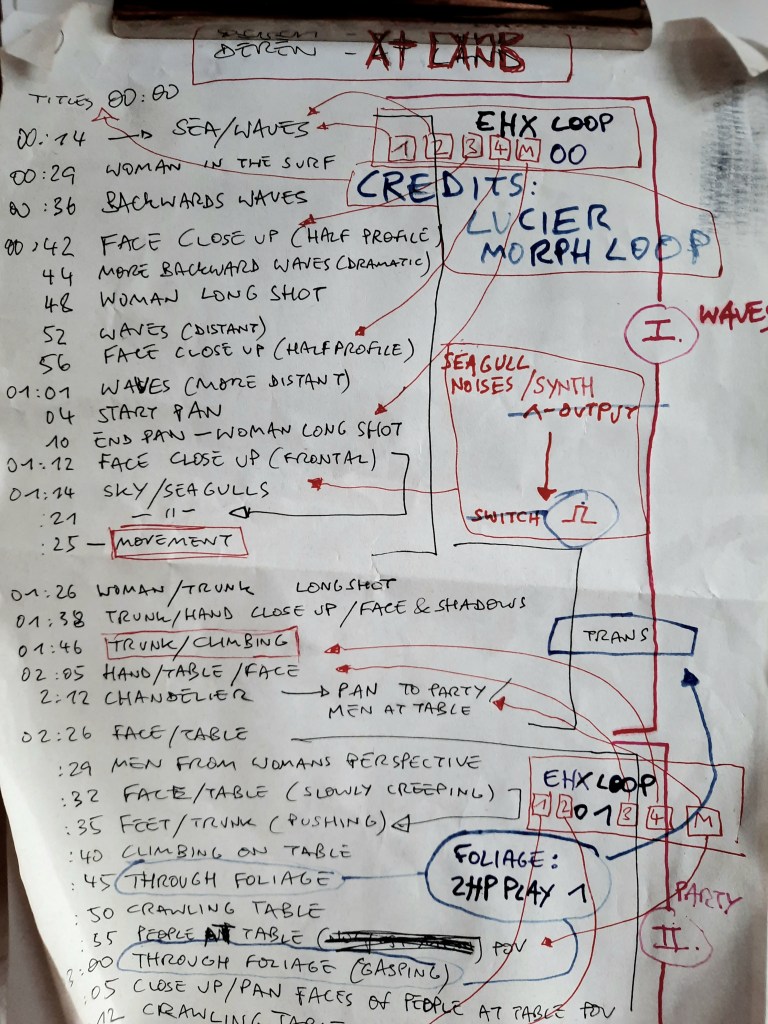

December 21 2025 marks the date that Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (Броненосец Потёмкин) has been in circulation for 100 years. For this anniversary I was commissioned by Flickertunes to compose a new score for the film. The screening/concert took place at City 46 cinema in Bremen on October 29, the score was played to a version restored by Deutsche Kinemathek that runs three minutes shorter than the Mosfilm version available on YouTube (but features a red flag colored by hand in two scenes as did the premiere version from 1925).

While working on the score, I felt compelled to charge the music with some sonic fragments of soviet and post-soviet history. There’s a music box that plays The Internationale (the soviet anthem until 1943), slowed down loops of various songs from the Russian revolution and civil war, samples from Elem Klimov’s 1984 film Come and See (audible during the mass panic in the Odessa Steps scene), a clicking sound taken from a soviet documentary on the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (when radiation strikes analogue recording media it produces audible clicks and visible flashes), field recordings of Russian AM-radio (recorded by Kris Kuldkepp in Lithuania, close to the Kalinigrad-exclave), a quotation of Yegor Letov’s 1988 punk song Vsyo idyot po planu (Everything is going according to the plan) in the finale of the film – a sentence that has been uttered by Russian officials during the war in Ukraine ad nauseam – and finally bits of speeches given by Vladimir Putin, Sergey Lavrov, Dmitri Medwedew and Alexandr Dugin during the past few years. These were put on tape loops and appear as the voices of czarist officers during the execution scene on the battleship.

Battleship Potemkin can be viewed both as a figurative and literal accumulation of history. It is a fictionalized dramatization of events that took place twenty years before its production and it has accumulated history over the past 100 years itself: Beatrice Vitoldi, an activist of Proletkult and later soviet attachée to Italy, was disappeared during Stalin’s Great Purge. She played the woman dressed in black who lets go of her baby carriage on top of the Odessa steps when shot by the Cossacks. Sergey Tretyakov, one of the screenwriters, took his own life in 1937 while awaiting trial for espionage in an NKVD prison. The introduction by Leon Trotsky was cut from the Soviet prints of the film after Stalin took complete control of the CPSU in the late 1920s. The film is haunted by its past, by 100 years of soviet and post-soviet history. It was censored, re-cut and banned in various countries for decades, in the Soviet Union it only found an audience because Vladimir Mayakovsky demanded its distribution.

Maybe even today there remains a weak charge of political energy buried in the rubble of this accumulated history. The Russian war on Ukraine will soon enter its fourth year. One of its causes is Vladimir Putin’s conception of history, his drive to rewrite it from a chauvinistic, paranoid and fascist perspective. The war has put another layer of meaning on the film, a rewriting of its historic palimpsest.

Maybe there’s also a hauntological presence connected to this film. The goal of evoking the sound of a bygone era, of conjuring a ghostly presence in the sonic field, is quiet obvious in the aesthetics choices made during the production of the score. The repurposing of recorded media from the past and the omnipresent sonic veil of radio static are related to what writers like Simon Reynolds, Mark Fisher et. al. dubbed hauntology in the 2000s. The nostalgia for a future that never came to pass seems shockingly out of date from today’s vantage though.

The predicament of a ‚lost future‘ has only intensified since the early 2000s: we inhabit a world that sheds possible futures on a daily basis, narrowing the range of prospective realities into one of an ever worsening dystopia. Referring to a loosely defined genre of mostly British electronic music with a focus on the uncanny and nostalgic (or scoring a 100 years old soviet propaganda movie) doesn’t seem like an adequate reaction to the stretch of history we are living through. Also, being nostalgic about the lost opportunities of the Russian revolution is at least double-edged: whatever historic circumstances and virtualities made it possible, they are unlikely to repeat. At the same time the monsters of state power that the revolution involuntarily birthed have very much survived to the present – from Cheka and NKVD to KGB and FSB; from Lavrentiy Beria to Vladimir Putin. Odessa today is not a backdrop for an attempted revolution but a target for Russian missiles and Shahed drones.

But there is an undeniable hauntology in the sense that Jacques Derrida gave to the concept when he coined it in the early 1990s. In Specters of Marx he outlines a political ontology of the present that is by necessity haunted by its past, by the spirits of failed revolutions and the horrors of history. In 1993 the political hegemony was marching to the ‚cadenced march‘ of “Marx is dead, communism is dead, very dead, and along with it its hopes, its discourse, its theories, and its practices. It says: long live capitalism, long live the market, here’s to the survival of economic and political liberalism!“ (Derrida 1994, p. 64). Versions of this song are still played today, even if every passing year and each of the mounting catastrophes make them shriller and more authoritative, as if to drown out the creaking noises of an economical and political order falling apart at the seams. Maybe it’s also a form of whistling in the dark. Being haunted by the ghosts of the past is by definition a scary thing.

As Derrida writes about ghosts: „[…] this thing that is not a thing, this thing that is invisible between its apparitions […]“ (Derrida 1994, p.6) …this thing can be considered as another name for the lingering effects of history on quotidian life. It lingers in books, photos and films, in people’s memories and the stories they tell (and also in their forgeries that the Stalinist bureaucracy produced); in the tics and transgenerational traumas of individuals and families, in the buildings and landscapes that surround us and also in the scars of those landscapes and people’s bodies, in the graveyards and anonymous mass graves. These signs and sites emerged from the historic process, were formed by it and are haunted by suppressed, forgotten and censored memories – and ghosts. As Mark Fisher writes: „Everything that exists is possible only on the basis of a whole series of absences, which precede and surround it, allowing it to possess such consistency and intelligibility that it does.“ (Fisher 2014, p. 21). Absence as a prerequisite for presence opens up the conceptual field of virtualities (“[…] think of hauntology as the agency of the virtual” – Fisher 2014, p. 22) and also the necessity of processing the past, to go through the necessary grief work in order to deal with it („Haunting, then, can be construed as a failed mourning. It is about refusing to give up the ghost or – and this can sometimes amount to the same thing – the refusal of the ghost to give up on us.” – Fisher 2014, p. 24). Mourning the dead will not bring them back but it will make life bearable.

The thing, the ghost, the specter of history for Derrida is inextricably connected to communism: “’Ein Gespenst geht um in Europa—das Gespenst des Kommunismus.‘ As in Hamlet, the Prince of a rotten State, everything begins by the apparition of a specter. More precisely by the waiting for this apparition. The anticipation is at once impatient, anxious, and fascinated: this, the thing (‚this thing‘) will end up coming. The revenant is going to come. It won’t be long. But how long it is taking.” (Derrida 1994, p. 2).

Clearly Putin is haunted by specters of the Soviet past as he has publicly stated that he sees the Ukrainian state as an invention of the Bolsheviks, a historic mistake that he needs to rectify by violent means.

The leaders of today’s nation states and corporations wouldn’t be as paranoid and malignant as they are if they wouldn’t feel haunted by the ghosts of past revolutions, by the specters of Marx. The Potemkin has left the harbor a long time ago. It will not return as a ghost ship, it will not save anyone ever again. But the remembrance of past revolts remains as a virtuality. Hope forever emerges from an impossible place stuck between the past and the future.

Derrida, Jacques (1994): Specters of Marx, New York/London: Routledge

Fisher, Mark (2014): Ghosts of my Life, Winchester/Washington: Zero Books